In machine learning, most problems can put in one of two categories: unsupervised learning and supervised learning. In supervised learning tasks, you know what classes your data points belong to, which means that you can check the performance of your classifier on your dataset. In contrast, in an unsupervised learning task you don’t have specific class labels for your data and it is often up to the researcher to come up with meaningful correlations and explore potential patterns in the dataset using statistical techniques like regression.

In this post, I’m going to demonstrate the process of taking a dataset and carrying out regression on the dataset in order to predict some possible trends using Scikit-learn in Python. The post will also demonstrate the process of visualizing data with Pandas, Seaborn, and Matplotlib.

For this post, we’ll be using the video game sales dataset, available HERE.

As you might expect, we’ll start off by importing all the libraries we will need.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt import pandas as pd import numpy as np import seaborn as sns from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression, ElasticNet, Lasso, Ridge from sklearn.tree import DecisionTreeRegressor from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestRegressor, AdaBoostRegressor from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler from sklearn.decomposition import PCA from sklearn.pipeline import Pipeline

Let’s start off by loading the data and checking the number of occurrences for features we might be interested in.

df = pd.read_csv("vgsales.csv")

# get an idea of the total number of occurences for important features

publishers = df['Publisher'].unique()

platforms = df['Platform'].unique()

genres = df['Genre'].unique()

print("Number of games: ", len(df))

print("Number of publishers: ", len(publishers))

print("Number of platforms: ", len(platforms))

print("Number of genres: ", len(genres))

Number of games: 16598 Number of publishers: 579 Number of platforms: 31 Number of genres: 12

We need to be sure that our data is free of any null values, so we’ll check for them and drop them if there are any.

print(df.isnull().sum()) # drop them if there are any df = df.dropna()

Rank 0 Name 0 Platform 0 Year 271 Genre 0 Publisher 58 NA_Sales 0 EU_Sales 0 JP_Sales 0 Other_Sales 0 Global_Sales 0 dtype: int64

One of the first things we may try doing is checking to see how many global game sales there are a year. We can count how many years there are in the database, then we can plot the years against the global sales.

# if we wanted the counts instead, we could just use Count. Count returns the number of instances,

# not the sums of the values like above

x = df.groupby(['Year']).count()

x = x['Global_Sales']

y = x.index.astype(int)

plt.figure(figsize=(12,8))

colors = sns.color_palette("muted")

ax = sns.barplot(y = y, x = x, orient='h', palette=colors)

ax.set_xlabel(xlabel='Number of releases', fontsize=16)

ax.set_ylabel(ylabel='Year', fontsize=16)

ax.set_title(label='Game Releases Per Year', fontsize=20)

plt.show()

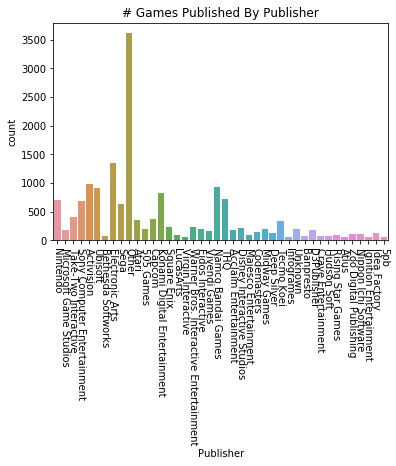

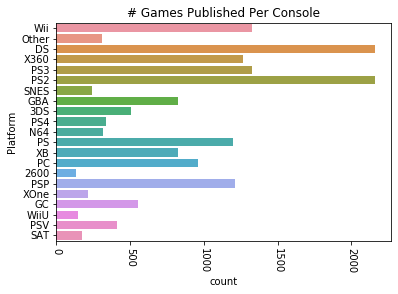

Let’s get an idea of how many games are published by specific publishers. There’s a lot of publishers in this list, so we want to drop any publishers that have published fewer than a chosen number of games. Let’s set 75 as a threshhold. We’ll also apply this same method to the platforms the games are published on.

After dropping much of the data, we can try plotting the remaining data that we’ve put into a new dataframe. We’ll plot the number of games published by both the most prolific publishers and the number published on different consoles.

vg_data = pd.read_csv('vgsales.csv')

print(vg_data.info())

print(vg_data.describe())

# let's choose a cutoff and drop any publishers that have published less than X games

for i in vg_data['Publisher'].unique():

if vg_data['Publisher'][vg_data['Publisher'] == i].count() < 60:

vg_data['Publisher'][vg_data['Publisher'] == i] = 'Other'

for i in vg_data['Platform'].unique():

if vg_data['Platform'][vg_data['Platform'] == i].count() < 100:

vg_data['Platform'][vg_data['Platform'] == i] = 'Other'

#try plotting the new publisher and platform data

sns.countplot(x='Publisher', data=vg_data)

plt.title("# Games Published By Publisher")

plt.xticks(rotation=-90)

plt.show()

plat_data = vg_data['Platform'].value_counts(sort=False)

sns.countplot(y='Platform', data=vg_data)

plt.title("# Games Published Per Console")

plt.xticks(rotation=-90)

plt.show()

RangeIndex: 16598 entries, 0 to 16597

Data columns (total 11 columns):

Rank 16598 non-null int64

Name 16598 non-null object

Platform 16598 non-null object

Year 16327 non-null float64

Genre 16598 non-null object

Publisher 16540 non-null object

NA_Sales 16598 non-null float64

EU_Sales 16598 non-null float64

JP_Sales 16598 non-null float64

Other_Sales 16598 non-null float64

Global_Sales 16598 non-null float64

dtypes: float64(6), int64(1), object(4)

memory usage: 1.4+ MB

None

Rank Year NA_Sales EU_Sales JP_Sales \

count 16598.000000 16327.000000 16598.000000 16598.000000 16598.000000

mean 8300.605254 2006.406443 0.264667 0.146652 0.077782

std 4791.853933 5.828981 0.816683 0.505351 0.309291

min 1.000000 1980.000000 0.000000 0.000000 0.000000

25% 4151.250000 2003.000000 0.000000 0.000000 0.000000

50% 8300.500000 2007.000000 0.080000 0.020000 0.000000

75% 12449.750000 2010.000000 0.240000 0.110000 0.040000

max 16600.000000 2020.000000 41.490000 29.020000 10.220000

Other_Sales Global_Sales

count 16598.000000 16598.000000

mean 0.048063 0.537441

std 0.188588 1.555028

min 0.000000 0.010000

25% 0.000000 0.060000

50% 0.010000 0.170000

75% 0.040000 0.470000

max 10.570000 82.740000

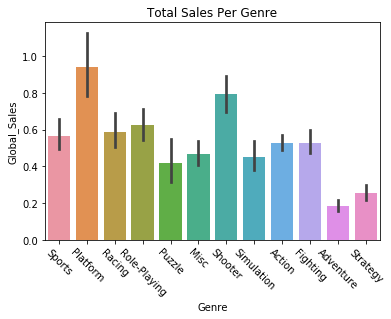

We can also try plotting variables against each other, like getting the global sales of games by their genre.

sns.barplot(x='Genre', y='Global_Sales', data=vg_data)

plt.title("Total Sales Per Genre")

plt.xticks(rotation=-45)

plt.show()

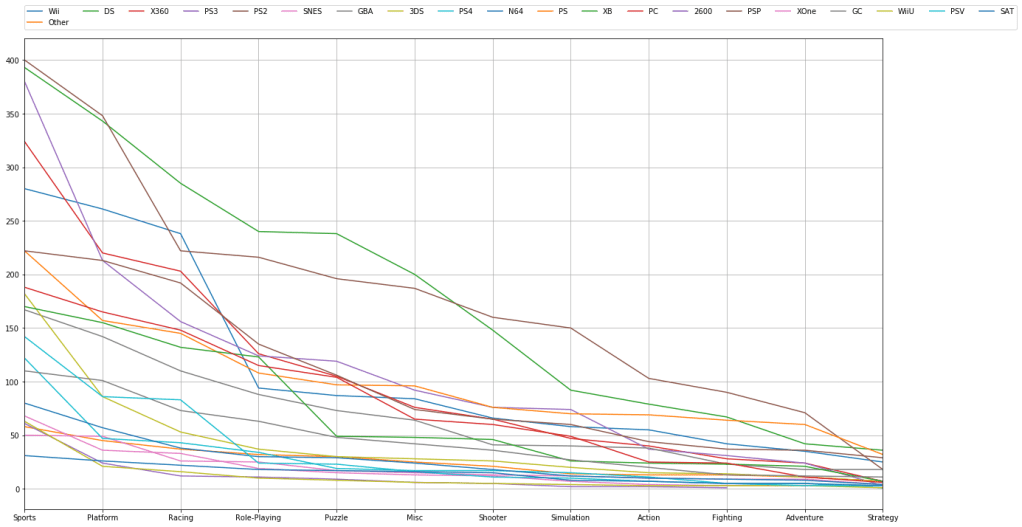

We can filter and plot by multiple criteria. If we wanted to check and see how many games are published in a given genre AND filter by platform we can do that. We just need to get the individual platforms, which we can do by filtering the “platform” feature with a “unique” function. Then we just have to plot the platform and genre data for each of those platforms.

# try visualizing the number of games in a specific genre

for i in vg_data['Platform'].unique():

vg_data['Genre'][vg_data['Platform'] == i].value_counts().plot(kind='line', label=i, figsize=(20, 10), grid=True)

# set the legend and ticks

plt.legend(bbox_to_anchor=(0., 1.02, 1., .102), loc=3, ncol=20, borderaxespad=0.)

plt.xticks(np.arange(12), tuple(vg_data['Genre'].unique()))

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Now that we’ve plotted some of the data, let’s try predicting some trends based off of the data. We can carry out linear regression to get an idea of how global sales figures could end up based on North American sales figures. First we need to separate our data into train and test sets. We’ll start by setting North American sales as our X variable and global sales as our Y variable, and then do train/test split.

# going to attempt to carry out linear regression and predict the global sales of games # based off of the sales in North America X = vg_data.iloc[:, 6].values y = vg_data.iloc[:, 10].values # train test split and split the dataframe X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=8)

The data needs to be reshaped in order to be compatible with Linear Regression, so we’ll do that with the following commands. We’re reshaping them into two long 2D arrays that have as many rows as necessary and a single column. After that we can fit the data in the Linear Regression function.

# reshape the data into long 2D arrays with 1 column and as many rows as necessary X_train = X_train.reshape(-1, 1) X_test = X_test.reshape(-1, 1) y_train = y_train.reshape(-1, 1) y_test = y_test.reshape(-1, 1) lin_reg = LinearRegression() lin_reg.fit(X_train, y_train)

LinearRegression(copy_X=True, fit_intercept=True, n_jobs=None, normalize=False)

Let’s check to see how our regression algorithm performed. We should plot the correlation between the variable’s training data, and plot the line of best fit from our regressor. We’ll then do the same thing for our testing data. Essentially we’re looking to see how the regression line fits both the training and testing data.

The regression lines should look approximately the same, and indeed they look fairly similar. The training set regression shows approximately 70 million sales for 40 million North American sales, while the test set regression may be just a little higher. We’ll also print the scores on the training and test sets, and see that our Linear Regression implementation had similar, though slightly worse accuracy on the testing set.

Let’s make a function to handle the plotting.

def plot_regression(classifier):

plt.scatter(X_train, y_train,color='blue')

plt.plot(X_train, classifier.predict(X_train), color='red')

plt.title('(Training set)')

plt.xlabel('North America Sales')

plt.ylabel('Global Sales')

plt.show()

plt.scatter(X_test, y_test,color='blue')

plt.plot(X_train, classifier.predict(X_train), color='red')

plt.title('(Testing set)')

plt.xlabel('North America Sales')

plt.ylabel('Global Sales')

plt.show()

plot_regression(lin_reg)

print("Training set score: {:.2f}".format(lin_reg.score(X_train, y_train)))

print("Test set score: {:.2f}".format(lin_reg.score(X_test, y_test)))

Training set score: 0.89

Test set score: 0.87

We can now implement some other regression algorithms and see how they perform. Let’s try using a Decision Tree regressor.

DTree_regressor = DecisionTreeRegressor(random_state=5)

DTree_regressor.fit(X_train, y_train)

plot_regression(DTree_regressor)

print("Training set score: {:.2f}".format(DTree_regressor.score(X_train, y_train)))

print("Test set score: {:.2f}".format(DTree_regressor.score(X_test, y_test)))

Training set score: 0.96 Test set score: 0.81

Now let’s try a Random Forest regressor algorithm.

RF_regressor = RandomForestRegressor(n_estimators=300, random_state=5)

RF_regressor.fit(X_train, y_train)

plot_regression(RF_regressor)

print("Training set score: {:.2f}".format(RF_regressor.score(X_train, y_train)))

print("Test set score: {:.2f}".format(RF_regressor.score(X_test, y_test)))

Training set score: 0.94

Test set score: 0.84

It looks like Random Forest and plain Linear Regression have comparable performance. However, we might be able to find a regression algorithm that performs better than these two. We’ll use a type of dimensionality reduction called Principal Component Analysis, which tries to distill the important features of a training set down to just the features that have the most influence on the labels/outcome. By reducing the dimensionality/complexity of a featureset, a representation that contains the features with the most predictive power is created. This can improve the predictive power of a regressor.

We’ll create a Scikit-learn Pipeline, which allows us to specify what kind of regression algorithm we want to use (Linear Regression) and how we want to set up the features for it (use the Standard Scaler and PCA).

Note that there’s only one feature we’re predicting off of here, North American sales, so PCA can’t simplify the representation anymore. But if we had more features we were doing regression on PCA could be useful.

components = [

('scaling', StandardScaler()),

('PCA', PCA()),

('regression', LinearRegression())

]

pca = Pipeline(components)

pca.fit(X_train, y_train)

plot_regression(pca)

print("Training set score: {:.2f}".format(pca.score(X_train, y_train)))

print("Test set score: {:.2f}".format(pca.score(X_test, y_test)))

Training set score: 0.89 Test set score: 0.87

We’re now going to try using different regression algorithms to see what kinds of results we get. Let’s try an Elastic Net regressor.

elastic = ElasticNet()

elastic.fit(X_train, y_train)

plot_regression(elastic)

print("Training set score: {:.2f}".format(elastic.score(X_train, y_train)))

print("Test set score: {:.2f}".format(elastic.score(X_test, y_test)))

Training set score: 0.54

Test set score: 0.51

Now let’s try Ridge regression.

ridge_reg = Ridge()

ridge_reg.fit(X_train, y_train)

plot_regression(ridge_reg)

print("Training set score: {:.2f}".format(ridge_reg.score(X_train, y_train)))

print("Test set score: {:.2f}".format(ridge_reg.score(X_test, y_test)))

Training set score: 0.89 Test set score: 0.87

Here’s a Lasso regression implementation.

lasso_reg = Lasso()

lasso_reg.fit(X_train, y_train)

plot_regression(lasso_reg)

print("Training set score: {:.2f}".format(lasso_reg.score(X_train, y_train)))

print("Test set score: {:.2f}".format(lasso_reg.score(X_test, y_test)))

Training set score: 0.38 Test set score: 0.36

Finally, let’s try using AdaBoost regression.

# ADA Boost regressor

ada_reg = AdaBoostRegressor()

ada_reg.fit(X_train, y_train)

plot_regression(ada_reg)

print("Training set score: {:.2f}".format(ada_reg.score(X_train, y_train)))

print("Test set score: {:.2f}".format(ada_reg.score(X_test, y_test)))

Training set score: 0.89

Test set score: 0.81

It looks like Ridge Regression and AdaBoost did the best at predicting the trend.

Thank you for reading through this demonstration of visualizing data and predicting data trends. If you’d like to go further and enhance your understanding of regression algorithms, I suggest checking the documentation for each of the algorithms in Scikit-learn. You can experiment with implementing these techniques on another dataset and altering the regression arguments.